Dear friend,

How are you?

I’ve been swinging between stoic, and a watery mess this week. I have just finished reading Evie Wyld’s extraordinary new novel, The Echoes, and now I am in my mother’s garden, my childhood home, weeping while watering the tomato plants. This is partly because Evie’s novel stretched bits of my heart open which I hadn’t known were closed. I am also deeply devasted about the girls in Southport who, attending a Taylor Swift themed dance class, were murdered when a 17-year old boy wandered in from the street and attacked them.

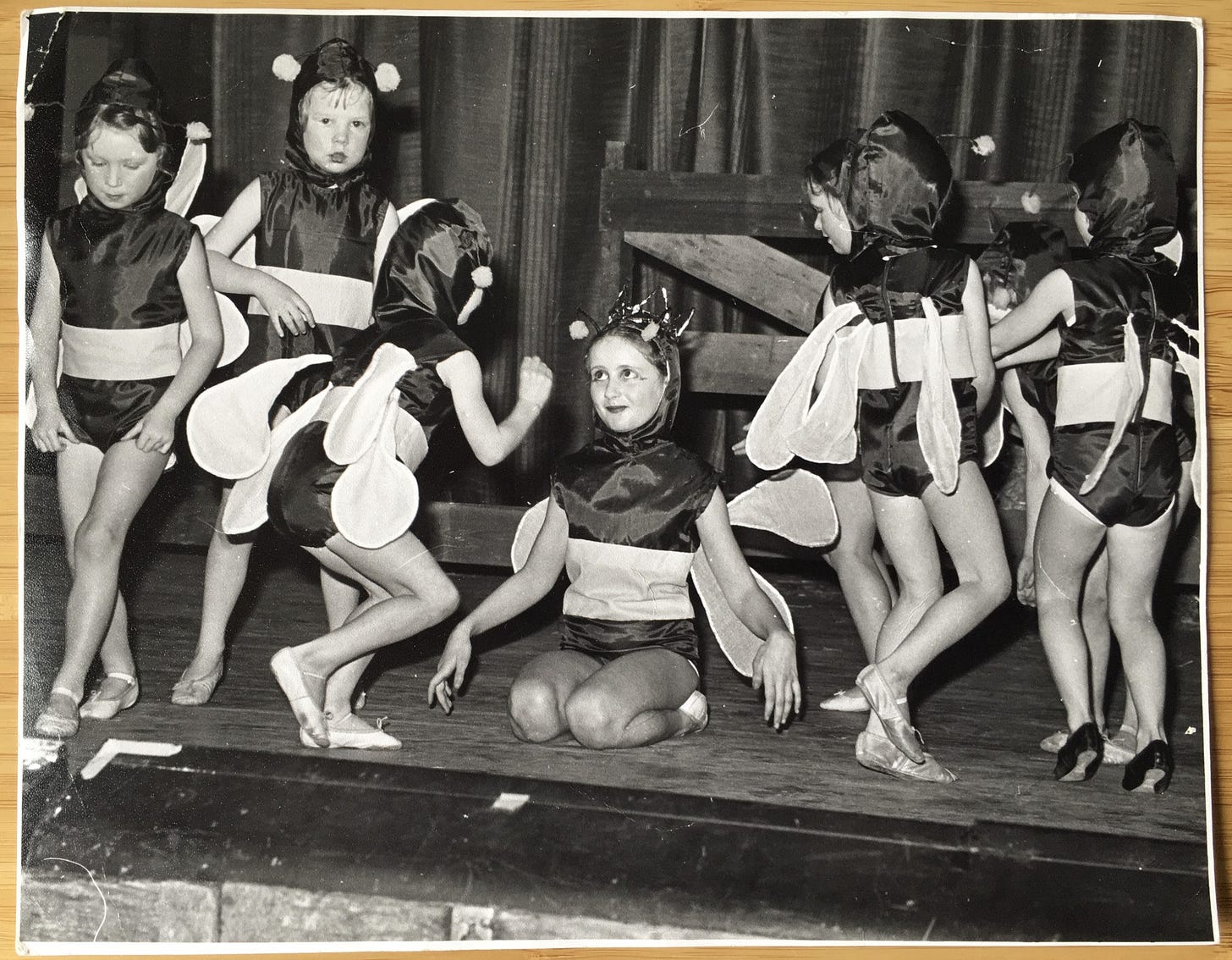

I was a dancing girl once. In the years since, I’ve learned that if you’re lucky enough to grow older, a jiggery slip of a former self, from your past, might seek you out. They might tap you on the shoulder, and say, ‘Hello-you. Remember me? Where have you put my dance shoes? I can’t find them!’

In my recently published memoir Lifting Off, about the 12 years I flew for British Airways, I wrote about a strange reconnaître* with a younger phantom self. Some time in the 2000s, I was in Los Angeles on a four day trip and, to stay awake (eight hour time change) I headed up to Redondo beach. In this particular trip, in the book, I describe how I was in a bad way: trapped in a job I hadn’t wanted in the first place, lost artistically, trying to manouevre my way into a more meaningful future. With all the boozing, I had lost something which couldn’t be articulated.

Here is an excerpt from Lifting Off when I am on the beach with my best cabin crew friend, Steve. We’ve just been to a supermarket to stock up with beer, which under Californian law is not allowed to be drunk in a public space:

Restocked, we headed for the beachfront houses over-looking Redondo beach. Painted in baby blues, creamy pinks and salmon hues, some were modernist structures with wide windows and spiral staircases leading up to roof gardens. Out front were dining spaces with tables, loungers and barbeques covered in plastic protectors. The beach was practically empty, and the houses all locked up. A few people played volleyball, while a group of teenage girls sat on a blanket. Gulls rested like pottery figures on the sand, their legs hidden under their chests. We headed towards a lifeguard tower and sat down, and I pushed my feet through the warm sand to find the cool underneath. Waves crashed into white foam, and we swigged beer from bottles in brown paper bags, checking over our shoulders for the police.

There were no swimmers, and soon the wet sand became silver. Moments later a light aircraft flew over in the sky with a sideways bottle of Malibu trailing behind, the lettering back to front. The New Malibu Island Melon. I watched the plane disappear remembering how, since childhood, I’d longed for a message in a bottle, but one washed up from the sea with a note rolled up in it. And now here one was: an advert for drink flying across the sky.

By six o’clock we’d finished the beers. As the sun dipped, the light in the east fell to blue, while the right sunk into orange. I rubbed my eyes awake. We had hours before bedtime, but without the sun the beach was losing its glory. Steve pulled me up and we took the wide stretch of sand back to the esplanade.

We moved along in a companionable silence, Steve a fraction in front, impatient for the night ahead, while I enjoyed the twilight. Joggers were out, and a skateboarder sped noisily by. It was then I noticed the familiar figure of a young girl up ahead, nine or ten years old, with blonde hair in bunches. As she got close, I registered her knock-knees and tanned calves. And when nearer still, how the right leg was covered with a square of gauze held by strips of medical tape. She was singing a song to herself, and I halted, letting Steve go on, knowing there was a presence about this girl. When she was about two metres away, I knew I shouldn’t have been staring so hard, so like a pervert, because now I had broken her song, and her eyes met mine. Her expres- sion was blank, waiting for me to speak, but I said nothing because I knew who she was.

In a photo album at home was a picture of myself on Brighton beach with my hair parted in the exact same way, a band either side making the bunches bouncy. On my right knee was a plaster where I’d fallen on the pebbles. I must have been nine or ten, wearing a little pink smock with a white lace trim around the neck. She was wearing a pink hoodie, little white shorts.

‘Hello,’ I said, softly, as she turned to look for someone. I knew what was coming next and lifted my hand to my nose and searched along the path. On cue a woman appeared, sunglasses, denim cut offs. Her mother.

‘Can I help you?’ she said. I knew she was going to reach swiftly for her daughter, then press her hand on her back, say ‘come on darling’ and move her along. I knew I would stay rooted to the spot and then say, ‘no you’re alright, I was just thinking about . . .’ and then I would go quiet because I could not say, not outwardly, something which would make me sound insane, like ‘I know this girl because she is me and there can be two of us and it’s nothing to be scared of.’

The déjà vu had taken hold and life taken on a texture of before, and again, and then all in the now. I waited for the scene to play itself out, waiting for the record to finish the track – I had no choice and didn’t want a choice because being in this moment was fascinating and assuring. At art college I had experienced many an occasion where I knew what was coming, just before it had. On cue, Steve turned and waved at me to hurry up and I shouted, while knowing I was going to shout, ‘I’m coming.’

‘You okay?’ Steve said, when I got to him. ‘You’re all pink.’

‘Tired,’ I said, the texture of the spell leaving me. ‘That girl, she looked just like me. I mean, I think she was me, when I was younger.’

‘You’re all over the place,’ he said, and slipped his arm into mine. ‘You probably need some water.’

At the end of the boardwalk, I turned to check for the girl. Her mother was holding her hand. Even though it didn’t make total sense, I knew we were meant to meet. When I got back to my hotel room, I would write it all down. It was important. The signs were coming for a reason. The first line would be: The message is not in the bottle, it is in the girl.

Back to the present day and the atmosphere in Mum’s garden gathers in intensity. I am now watering the rhubarb, even though there might be heavy rain later. Like hawthorn, which grows by taking up the space it is given, the rhubarb plant has spread its giant trumpet leaves. When my older sister Dawn was little, and I was not yet conceived, she was given the choice of bedrooms: the small box room with a view of the road, or the larger back room overlooking the garden. Dawn chose to grow up in the box room. Now, in height, she is less than five foot one. Whereas, through no choice of my own, I got the largest room and am now five foot eleven. As they say, go figure.

Eating freshly plucked, soft ripe raspberries, I remember the heat of my teenage summers here. Then I would’ve been in my bikini, on a padded reclining chair, trying for no tan lines. It was never comfortable, the hot spongy material against skin. There would have been an urge for an ice lolly, or something else altogether out of reach, my legs too lazy to move. I would’ve obsessed over how my chubby thighs pressed together and wished them into bean poles. Then, I would spread out a towel, and lay on my back and watch a plane cross the sky. The grass would itch and I would dream that someone was gazing out their window down at me. I wanted them to see I was nearly naked and I yearned for this unknowable person to want me.

As I drum water against the rhubarb leaves, I recall how Dawn told me this same spot is where Dad had planted his rhubarb. I have no memory of this; plants being the least interesting thing in my childhood compared to Tammy dog dressed up in vest and pants, and Tammy cat who avoided the hats and costumes I had ready for her.

The other day Mum’s friend Isabelle told me I used to enjoy helping my dad water the plants, that I loved digging with my little blue spade. I really don’t remember this, though it heartens me to know I was alongside him.

Forty-five years on and out of my heart grows a garden. I am fifty-two now, and I am missing digging up the past. I want to be back in the world of writing Lifting Off. Now the book is out in the world, I miss Dad more than ever. I went from feeling such anger, and now I’ve written about him and Mum, and understood him and his drinking, released all the hurt and shame through the writing process, now I have nothing but love, mixed up with the echoes of him here, curled into the shells of garden snails.

Mum rings my phone from the front room.

‘Are you still here?’

The complexity of this question is not lost on me. I go inside to the lounge.

‘I’m still here,’ I say.

‘I was testing the phone,’ she says. Then she studies the TV guide to get her bearings. ‘The carers will be here at five.’

‘Correct,’ I say. She is wearing a red winter jumper. In this heat. Her face is pink and shining from sweat. She will not have the window open, or the fan switched on.

‘I’d like to put you in a summer top, Mum,’ I say. ‘Nurse’s orders.’ She was ill the evening before and a 111 nurse called me back to explain this sickness was probably down to the intense heat.

In the end Mum gives in. She lifts her arms and I pull off the jumper, the heat and static held in the material, and yank down a flowery top over her bra-less figure. In a vase are red roses from her garden. I never liked this flower before. Oh Rose thou art sick. Reminds me of a cheesy Valentine’s Day when I had sex with someone I didn’t fancy. Now I think their form is quite wonderful. I see how they grow and die. I notice how they begin and store their energy in protective balls over winter.

Nevertheless I am working on a new novel. It is not easy getting into a new world. But I trust it will begin to inhabit me soon. One thing I do do, to make the project more concrete is, I write myself a letter all about the book, my fears around the writing of it, and the actions I will take to make it happen.

This letter solidifies it all. It’s now a forecast. Like a newly planted seed, although hidden from view for sometime to come, it’ll remain dormant until conditions are favourable for germination, which is when the seed breaks open and becomes a seedling.

After, I lick the envelope and pass the letter to Min for safekeeping. I explain she is to hand it back to me in a year’s time. She nods, then sets her alarm on her phone for 04.08.2025.

Write soon, write yourself that letter to open in a year; write often.

Much love,

Karen xxx

This Substack is supported by paying subscribers, so if you are able to, please upgrade to a paid subscription:

*In French ‘reconnaître’ means ‘to recognise’. With French words I like to break them open to examine their meaning. ‘Naitre’ means to be born. So join this with recon, my translation of this word is, a reconnection with birth, or a re-knowing, or a retrieval of a part of a missing self. Reconnaître.